Sugarfork: A Historic Cherokee Valley

Sugarfork is a secluded mountain basin nestled in the southeastern corner of Macon County, North Carolina, shaped by the cool, clear waters of Walnut Creek, Ellijay Creek, and Ledford Branch—all tributaries that ultimately merge into the Cullasaja River, one of the most vital arteries of the Cherokee Middle Towns. The valley’s unique topography—flatlands encircled by protective ridgelines—made it an ideal location for early human habitation, seasonal migration, and subsistence agriculture long before European maps ever named it.

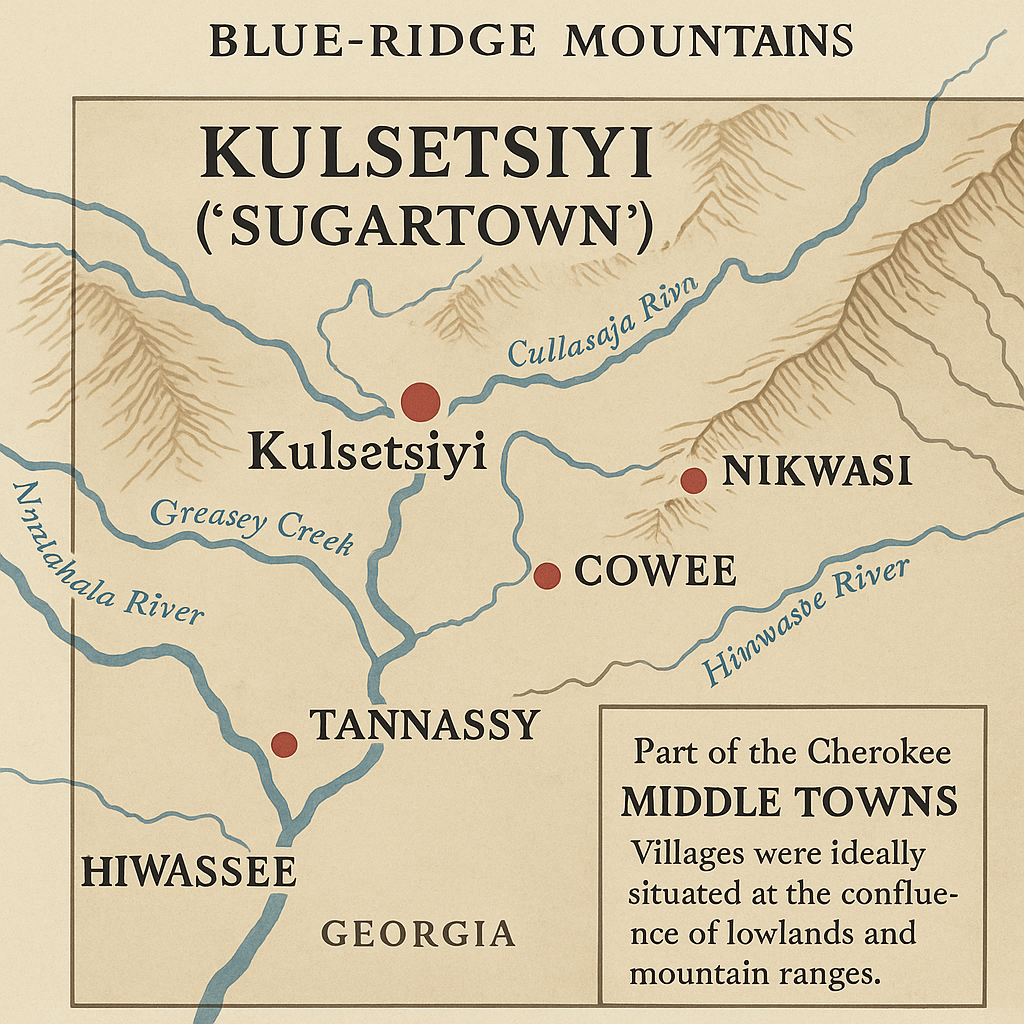

This region is believed to be one of several ancestral Cherokee settlements historically known as Kulsetsiyi (ᎫᎳᏎᏥᏱ), often translated as the “Place of the Honey Locust.” The name refers not only to the honey locust tree—a native species valued by the Cherokee for its sweet edible pods, nitrogen-fixing properties, and soil regeneration benefits—but also to the larger cultural context of sweetness, sustenance, and renewal associated with these fertile mountain basins.

As white settlers arrived and began mapping the region, Kulsetsiyi became Anglicized to Sugartown, a name that was eventually applied to multiple Cherokee communities across the Southern Appalachians. While other towns with the same name appeared along the Keowee River in South Carolina and near Sugar Creek in North Georgia, the geographic, botanical, and linguistic markers surrounding this particular valley—now called Sugarfork—strongly suggest it as one of the most authentic and original Sugartown settlements in the historical Cherokee heartland.

The very landscape seems to affirm this legacy. The Sugarfork Valley sits at a crossroads of elevation and abundance, where highland ridges give way to rich alluvial fields, and spring-fed creeks braid together the stories of those who walked this land. The Cullasaja River, into which these waters flow, has long been considered a “river of sweet water”—its name derived from the same Cherokee root as Kulsetsiyi—making the Sugarfork basin part of a broader ecological and spiritual corridor that shaped indigenous life for centuries.

This section begins a deeper, more intimate exploration of Sugarfork Valley’s long memory—its Cherokee origins, its environmental character, and its evolving cultural role within the greater story of the Southern Appalachian region. It is a place of continuity as much as change, where ancient footpaths once followed planting moons and where today’s trails may still echo with the soft cadence of remembered songs.

Kulsetsiyi: Heart of the Hidden Valley

Long before Sugarfork appeared on any map, before boundary lines were drawn and deeds were inked, this land was known as Kulsetsiyi—“Sugartown” in the Cherokee language. The name comes from the sugar maple trees that once flourished in the cool hollows and upland slopes of this secluded valley, tapping into the rhythms of the land with their sweet sap and vibrant seasonal cycles.

Long before Sugarfork appeared on any map, before boundary lines were drawn and deeds were inked, this land was known as Kulsetsiyi—“Sugartown” in the Cherokee language. The name comes from the sugar maple trees that once flourished in the cool hollows and upland slopes of this secluded valley, tapping into the rhythms of the land with their sweet sap and vibrant seasonal cycles.

Kulsetsiyi was not a major Cherokee mound center like Nikwasi or Cowee, but it was part of their sacred orbit—a satellite settlement nestled in a protective bowl between ridgelines. It served as a seasonal dwelling ground, a sap and herb gathering station, and a farming enclave, where families lived in harmony with the land during times of planting, harvesting, and ceremony. The creek-fed terraces and open meadows we see today echo those ancestral patterns.

This wasn’t wilderness. This was homeland.

The Cherokee word kulsetsi refers specifically to sugar or maple sap, but its deeper resonance lies in its connection to community. Kulsetsiyi was not just about a tree or a product—it was about place. A place where people gathered, rested, grew, and passed stories through generations. A place of abundance, clarity, and connection. A place where medicine grew from the earth and wisdom flowed through water.

Today, archaeological traces may be faint—few carved stones, no towering mounds—but the land speaks in subtler ways. The broad terraces near the creeks, the strategic sightlines between peaks, the level basins that would have supported crops and gatherings—all point to long-standing human presence. Even now, old growth root systems and forgotten footpaths whisper stories to those who listen.

To invoke the name Kulsetsiyi in modern development is to reverently acknowledge this deeper memory. It is to say:

We see you. We remember.

We walk gently on the bones of the old village.

In honoring Kulsetsiyi, your eco-resort is not just building for the future. It is restoring the past—preserving a sacred place where the heartbeat of the Cherokee Heartland still echoes in the rustle of maple leaves and the rush of Sugarfork Creek.

The Cullasaja River: Artery of Sweet Water and Sacred Geography

Winding through steep gorges and fertile lowlands, the Cullasaja River has always been more than a body of water—it has been a cultural and ecological lifeline. Its name comes from the Cherokee word Kulsetsi, meaning “Sweet Water”—a name that reflects not only its clarity and taste, but its life-giving presence throughout the Cherokee Middle Towns.

The Cullasaja linked Nikwasi, Cowee, and surrounding settlements into a cohesive corridor of ceremony, agriculture, and trade. From its highland tributaries to its confluence with the Little Tennessee River, the Cullasaja served as both a travel route and a sacred boundary, guiding seasonal migration, planting cycles, and diplomatic movement.

Among its tributaries is Sugar Fork, itself a branch of sweet water. Though smaller, Sugar Fork carried the same essence—nourishing hidden basins like Walnut Hills, where natural springs bubbled up into farm terraces and maple-rich hollows. Together, these waters formed an interconnected system, where river and ridge, floodplain and field, all coexisted in an intentional, reciprocal relationship.

To restore this land today is to recognize that water holds the memory. The Cullasaja and Sugar Fork are not just waterways—they are the living conduits of memory, balance, and belonging, in a place where every stream once carried story.

Though smaller and less formally recorded than its sister tributaries, Sugar Fork Creek is real—a name carried through oral tradition, valley naming, and ecological memory. Emerging from springs and hollows within the Sugarfork Basin, its waters feed into Walnut Creek and echo the lifeways of those who once lived along its banks. More than a mapped stream, Sugar Fork represents a network of seasonal flows and hidden sources, nourishing the land as it always has. Today, these subtle waterlines remind us that not all rivers of meaning are printed on maps—some live through story, soil, and the memory of place.

Nikwasi and Cowee: The Mound-Building Centers

Nikwasi, now partially preserved within the town limits of modern-day Franklin, North Carolina, was once among the most influential towns of the Cherokee Middle Towns. Its massive earthwork platform mound—still visible today—was more than just a remnant of the past. It served as both literal foundation for the council house and symbolic anchor of community identity, governance, and sacred continuity. Cowee, located just a few miles downriver along the Cullasaja, functioned as a spiritual and political counterpart. Together, these towns defined a stretch of river valley that was far more than geographic—it was ceremonial terrain, deeply embedded in the rituals and lifeways of the Cherokee people.

These sites were not chosen by accident. The alignment of Nikwasi, Cowee, and related mounds along the Cullasaja River reflects a sophisticated understanding of landscape, energy, and connectivity. The river was a lifeline of exchange and migration, and the mounds were placed at nodes of natural power—flat terraces above flood level, near fertile ground, and surrounded by protective hillsides.

The mounds themselves weren’t simply piles of dirt. They were sacred structures—constructed layer by layer over many generations, using packed clay and ceremonial fill. Each layer represented a cycle of renewal, often coinciding with leadership transitions, seasonal festivals, or the rebuilding of the town house. These townhouses, built atop the mounds, functioned as council chambers, gathering places, and spiritual centers—spaces where political decisions were made, sacred fires were kept, and oral traditions were passed on.

Beyond their monumental cores, these towns maintained concentric rings of influence. Radiating outward from the mounds were agricultural plots, artisan workshops, family homes, and sacred groves. Further still were satellite communities—like Sugartown (Kulsetsiyi)—which offered upland farming zones, seasonal foraging areas, and spiritual retreat spaces. These zones were not peripheral, but essential. They created a living network between river valleys and ridgetops, where highlands like Walnut Hills were intrinsically tied to the ceremonial heart of towns like Cowee and Nikwasi.

To understand or restore this land today requires more than just mapping old trails or identifying mound sites. It means recognizing the interwoven relationship between geography and community, between landform and lifeform. Walnut Hills is not simply adjacent to history—it is part of a system that once pulsed with ritual, memory, and movement. Any act of conservation or interpretation today is not just about preserving buildings or artifacts—it’s about honoring the ancestral geometry of life that once flowed between river and ridge, mound and mountain, memory and meaning.

Echoes Through Time: Colonial Conflict and the 1819 Cession

As European settlers pushed deeper into the Appalachian interior during the 18th century, Cherokee lands became the focus of increasing pressure—military, political, and economic. The Southern Appalachian foothills, rich in water, timber, and arable valleys, were seen not only as resources to be exploited but as obstacles to settler expansion. The Cherokee, long stewards of this land, found themselves targeted by a rising tide of colonial aggression.

In 1776, during the height of the American Revolution, colonial militias launched a series of devastating campaigns against the Cherokee Middle Towns. These attacks were not random; they were strategic, designed to break the logistical and spiritual centers of Cherokee society. Towns like Nikwasi, Cowee, and others throughout the Cullasaja and Little Tennessee watersheds were burned, looted, and dismantled. Crops were destroyed. Livestock slaughtered. Sacred structures razed. The goal was not just to defeat a military threat, but to erase a people’s relationship to place.

Despite this onslaught, the Cherokee endured. They rebuilt. They retreated deeper into the mountains, into places like Sugarfork, where secluded hollows and defensible ridgelines offered safety and continuity. The oral traditions, plant knowledge, and land relationships did not vanish—they adapted, carried forward through memory, kinship, and resilience.

Yet the policy of removal continued. Treaties signed under duress chipped away at Cherokee territory year by year. And in 1819, a defining moment arrived. Under the Treaty of 1819, the Cherokee Nation ceded nearly all remaining lands in what is now Macon County. With the stroke of a pen—and under immense pressure from both federal agents and encroaching settlers—millennia of land stewardship were legally stripped away.

This included the Sugarfork basin, which had likely served as a seasonal gathering place, farming area, and spiritual refuge for generations. The land passed into settler hands, where it was surveyed, subdivided, and renamed. But beneath the new names and borders, the old knowledge remained. You can still trace planting terraces along creek bends. Game trails still follow ancient footpaths. Springheads and sacred groves still whisper stories in the wind.

To walk this land today is to walk through layers of conflict and continuity. The 1819 cession marked a turning point, but not an end. The Cherokee spirit—rooted in relationship, place, and reciprocity—was never fully removed. And those who now seek to restore and steward these lands have an opportunity not just to honor history, but to reconnect with it in tangible, respectful ways.

Sugarfork Baptist Church: 1867 and the New Valley Identity

In the wake of the 1819 Cherokee land cession, the landscape of Sugarfork Valley entered a new and complex chapter—one marked by both continuity and change. As the Civil War drew to a close and Reconstruction began reshaping the South, settler families began to formalize their presence in the valley with institutions that would define their communal identity for generations.

Founded in 1867, Sugarfork Baptist Church stands as one of the earliest recorded social and religious establishments in the valley following the forced removal of Cherokee inhabitants. In a time when roads were still little more than wagon tracks and mail delivery an occasional event, the church became far more than a place of worship. It was a center of ritual, gathering, and mutual support. Marriages were consecrated under its rafters. Departed elders were mourned in its pews. Children were baptized in its creekside waters, and families gathered for community meals, harvest blessings, and seasonal singing.

Constructed with locally harvested timber and likely sited near a spring or natural crossroads, Sugarfork Baptist reflected the practical sensibilities of Appalachian settlement. Yet it also marked a symbolic transition: from Cherokee stewardship to settler permanence, from oral tradition to written scripture, from shared land to titled property. This shift was not just cultural—it was spiritual, economic, and ecological.

Importantly, the church’s founding did not occur on a blank slate. The valley it claimed had already been cultivated, walked, and revered for countless generations. The springs it relied on had watered Cherokee crops. The groves surrounding it once held sacred trees. And the soil beneath its cemetery bore the unseen traces of lives and ceremonies that predated it by centuries.

Today, remnants of the original Sugarfork Baptist Church site still remain—stone markers, weathered timbers, and sunken earth where structures once stood. These artifacts are not merely historical curiosities; they are touchstones in a palimpsest, where each generation writes over the last but never fully erases it. In this layered history, settler and Cherokee, sacred and secular, old and new all share the same terrain.

To honor Sugarfork’s story is to recognize that the church was both a sign of resilience for the post-war mountain community and a silent witness to the deeper legacies that came before. As Walnut Hills and the broader Cedar Knob Legacy Preserve take shape, these stories—written in pine boards, sandstone slabs, and memory—remain vital to understanding how identity, place, and spirituality continue to evolve in the valley.

Geography as Destiny: The Walnut Hills Basin

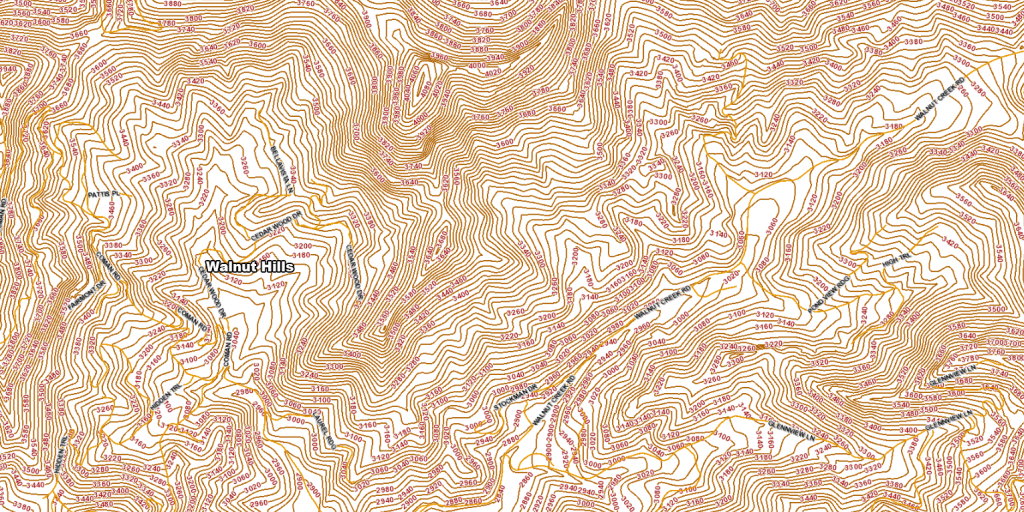

Modern topographic analysis confirms what earlier peoples intuitively understood: Walnut Hills lies within one of the rare, gently sloping mountain basins nestled deep in the rugged Sugarfork terrain. Framed by high ridgelines on three sides, the basin serves as a natural cradle—shielded from harsh weather, yet open enough to catch the sun and channel water from the surrounding slopes.

Unlike the steep gorges and narrow hollows that define much of Macon County, this basin offers a rare balance of elevation, shelter, fertile soils, and perennial springs. Several branches converge here—Ledford Branch from the southeast, Walnut Creek from the northeast, and highland springs bubbling out from sandstone shelves that have filtered water for millennia.

Long before land deeds and topographic maps marked its boundaries, this site likely functioned as a seasonal agricultural ground for Cherokee communities. The geography would have made it ideal for the “Three Sisters”—corn, beans, and squash—cultivated together in a triad that sustained both nutrition and soil fertility. Terraced by nature and sustained by springs, the land likely also produced wild ramps, bloodroot, and other medicinal or ceremonial plants gathered by hand and passed on through oral tradition.

Even today, walking the Walnut Hills property reveals signs of intentional use: wide level fields between wooded ridges, game trails worn into soft earth, stone clusters that suggest older boundaries or planting zones. These clues do not shout—they whisper, waiting to be heard by those willing to listen with both heart and history in mind.

In ecological terms, Walnut Hills offers a microclimate unique within the Cullasaja River watershed. Its protection from winter winds and its mild southern exposure allow for a growing season that outlasts surrounding elevations. This is the essence of the “thermal belt” once studied by Silas McDowell—an area where apples thrived and medicinal herbs flourished under watchful mountains.

Today, this same geography makes Walnut Hills a cornerstone for regenerative agriculture, sustainable forestry, and place-based tourism. It is not just a development site—it is a living landform with memory, a basin that cradles not only water and crops but also stories, ceremonies, and the future possibility of ecological harmony.

Silas McDowell: Apple Trees and the Thermal Belt

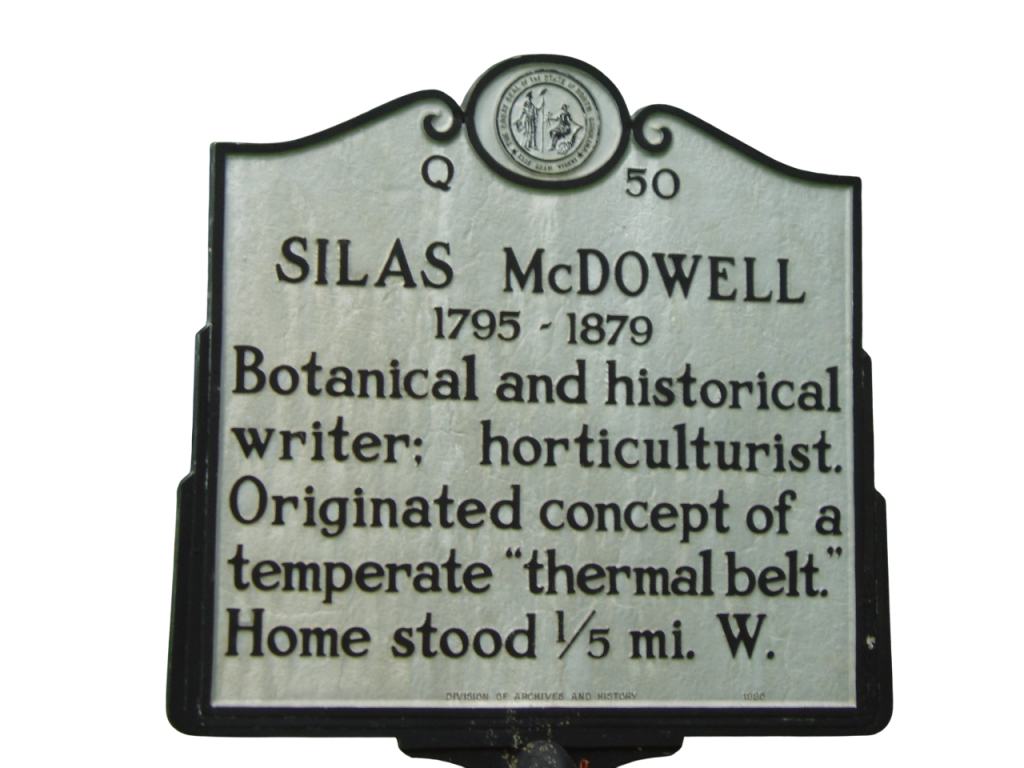

Silas McDowell (1795–1879) was more than a homesteader—he was one of Appalachia’s earliest land-based scientists, a self-taught naturalist, farmer, writer, and philosopher who documented the landscapes of Macon County with uncommon clarity. Living in the heart of the Southern Highlands, McDowell dedicated his life to understanding how climate, elevation, slope, and soil intersected to shape the lives of both plants and people.

Silas McDowell (1795–1879) was more than a homesteader—he was one of Appalachia’s earliest land-based scientists, a self-taught naturalist, farmer, writer, and philosopher who documented the landscapes of Macon County with uncommon clarity. Living in the heart of the Southern Highlands, McDowell dedicated his life to understanding how climate, elevation, slope, and soil intersected to shape the lives of both plants and people.

https://highlandshistory.com/exhibits/walk-in-the-park/walk-in-the-park-2006-silas-mcdowell

Among his most enduring contributions was his articulation of the “thermal belt,” a term still used by agronomists today. He noticed that along certain elevations, typically between 2,000 and 3,000 feet, frost was less likely to settle, allowing fruit trees and delicate perennials to thrive where they would otherwise perish. This narrow ribbon of temperate air across mountain slopes became known as the optimal zone for apple orchards, vineyards, and healing plants—a discovery that positioned Western North Carolina as an early leader in mountain horticulture.

McDowell helped introduce new apple cultivars into the region, encouraging settlers and mountain farmers to establish orchards on mid-slope terraces. His advice guided generations of growers and influenced traveling botanists who came to study the region’s biodiversity. He was also among the first to advocate for reforestation and soil regeneration at a time when clear-cutting and soil exhaustion were rampant across the Blue Ridge.

Perhaps most striking was his instinct for geomorphology—decades before it was formalized. He carefully mapped slope instability and natural scars, including the vast hillside shear east of Walnut Hills, now colloquially known as the McDowell Slide. This feature stands today not just as a geological anomaly, but as a reminder of the delicate balance between topography and stewardship.

McDowell published essays and land observations in both regional newspapers and scientific journals, calling on settlers to work with the land rather than against it. He was a rare voice in the 19th century: equal parts conservationist and practitioner, philosopher and farmer.

Today, his legacy lives on in the ecological vision of Walnut Hills. By honoring McDowell’s insights, your project aligns with a deeper Appalachian wisdom—one that values place-based knowledge, long-term land health, and the gifts of the thermal belt. The reintroduction of honey locust trees, the cultivation of heirloom apple varieties, and the use of slope-informed building and planting plans all echo his foresight.

The wind that rustles through Walnut Hills carries more than pollen and birdsong—it carries the whispers of those who once walked its ridgelines with curiosity, reverence, and care. Silas McDowell was one of them, and his footsteps remain etched into the slope lines, orchard rows, and conservation ethos that guide this next chapter.

The Next Chapter: From Sacred Past to Stewarded Future

The history of SugarFork does not end with its rediscovery—it begins a new chapter under the guidance of two aligned efforts: the Walnut Hills Conservancy Preserve and the Cedar Knob Legacy Preserve.

Together, these initiatives form the backbone of a long-term land stewardship vision that respects the valley’s sacred origins while preparing it for a sustainable, community-centered future. Rooted in conservation, ecological restoration, and cultural respect, these preserves are not developments in the traditional sense—they are acts of preservation and redefinition.

Walnut Hills Conservancy Preserve

Spanning over 150 acres of ridgelines, creeks, and native forest, Walnut Hills is committed to protecting the ecological core of SugarFork Valley.

Key efforts include:

-

Protection of native waterways like Ledford Branch and Walnut Creek

-

Restoration of historic plant systems including honey locust, chestnut, and medicinal flora

-

Low-impact trails and cabins designed to blend with the landscape, not impose upon it

-

Educational programs and workshops to reconnect people with the land’s deeper story

Cedar Knob Legacy Preserve

Located on one of the highest and most symbolic points of the land, Cedar Knob stands as a marker of continuity—a place where views stretch beyond state lines, and vision stretches beyond this generation.

The preserve will include:

-

A private, sacred trail system (Nvnehi Trail) offering over a mile from Grindstone Knob to Cedar Knob, leading to the base trail in Walnut Hills and the Nantahala National Forest

-

Forest-based recreation including disc golf and primitive camping

-

Naming-rights and legacy sponsorships to tie families and individuals into the land’s future

-

Long-term protection of cultural and ecological zones across the SugarFork ridge system

Legacy With Intention

What began as an overlooked mountain hollow is now emerging as a model for rural conservation, ecological design, and historical acknowledgment. By honoring the Cherokee story of Kulsetsiyi and aligning future use with conservation-first principles, Walnut Hills and Cedar Knob are ensuring that SugarFork remains protected, relevant, and alive for generations to come.

This is not development.

This is regeneration—cultural, ecological, and communal.